- FHCQ Foundation for Health Care Quality

- COAP Care Outcomes Assessment Program

- Spine COAP Care Outcomes Assessment Program

- SCOAP Care Outcomes Assessment Program

- OBCOAP Care Outcomes Assessment Program

- CBDR

- Smooth Transitions

- WPSC Patient Safety Coalition

- Bree Collaborative Bree Collaborative

- Health Equity Health Equity

- Admin Simp

- Contact Us

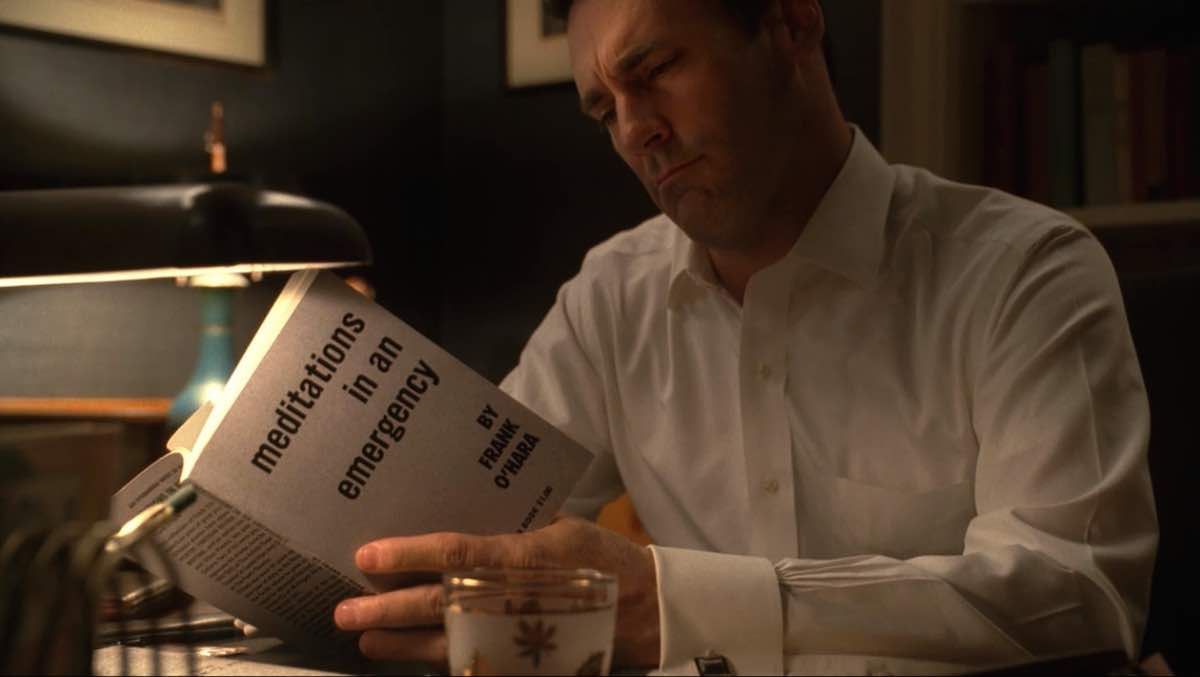

The Opioid Crisis: Meditations in a Public Health Emergency

The Opioid Crisis: Meditations in a Public Health Emergency

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

On October 26th, the White House declared the opioid crisis a National Public Health Emergency.

This act fulfilled a long-standing campaign promise of the president, with one seemingly small, but significant modification: the declaration of a National Public Health Emergency, not just a National Emergency.

While this may sound like a simple semantics issue, with one being an abbreviation or umbrella term for the other, in reality these are two distinct terms with considerable differences.

For this reason, the choice to classify the opioid crisis as a National Public Health Emergency left some satisfied, while leaving others to worry that what could have been a giant leap for a harrowing epidemic had been demoted to only a small step.

So, how do these two terms differ, and what could it mean for the handling of the opioid crisis?

To start, below is a breakdown of the two terms:

|

National Public Health Emergency (NPHE) |

National Emergency (NE) |

| Public Health Emergency*: A determination that “(1) a disease or disorder presents a public health emergency; or (2) a public health emergency, including significant outbreaks of infectious diseases or bioterrorist attacks, otherwise exists.” * The term Public Health Emergency appears to be interchangeable with National Public Health Emergency. |

National Emergency: “A situation beyond the ordinary which threatens the health or safety of citizens and which cannot be properly addressed by the use of other law.” |

| An NPHE is technically declared by the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the current secretary being Eric Hargan. The president also can direct the secretary to declare an emergency, as he’s done here. | An NE is declared by the president and only the president. |

| An NPHE is supported by Public Health Services Act. | An NE is supported by the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. |

| An NPHE designation allows the administration to allocate money from the Public Health Emergency Fund, which for the moment is nearly empty. | An NE requires the administration to allocate funds from FEMA. |

| As Matt Lloyd, an HHS spokesperson, told ABC News on October 26th, the Public Health Emergency Fund currently holds about $57,000. As House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said in response to the declaration, and others echoed: “Show me the money.” Congress will need to vote to refill the Public Health Emergency Fund in order for the administration to act on the opioid crisis. The White House says they’re working with Congress to make this part of an end-of-year budget negotiation. | FEMA has an annual budget of $13.9 billion. Though it’s been hit hard by the recent swath of major hurricanes, the fund remains larger than the Public Health Emergency Fund by many margins. |

| An NPHE declaration is generally seen as applying to a lesser event than an NE in that it triggers a comparatively smaller, slower response than an NE. NPHEs are often applied to infectious disease outbreaks and major storms. According to this article, there have been 20 NPHEs since 2005, if you count the opioid crisis (scroll to the second red list), almost all of them concerning weather events. | NEs are generally seen as applying to larger events, including natural disasters and threats of terrorism and, as NPR White House correspondent Tamara Keith told David Greene, “are more specific to a point in time and a specific location.” There are currently 28 active NEs; interestingly, almost all of them applying to international violence and disruption. |

| NPHE declarations allow certain regulations to be waived, certain laws to be eased, and some federal grant money to go toward addressing the emergency. | A national emergency triggers a rapid disbursement of federal funds to address it and allows the president to execute major operations like activate the National Guard. |

.

Pelosi to Trump on declaring the opioid epidemic a public health emergency: “Show me the money.” (via ABC) pic.twitter.com/4zJPX6V0Yq

— Kyle Griffin (@kylegriffin1) October 26, 2017

FOUR WAYS THE DECLARATION COULD BENEFIT THE OPIOID CRISIS

On November 1st, the Opioid Commission led by New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie issued its long-awaited recommendations for handling the opioid crisis as an NPHE. You can read a good summary of the report here and the full report here.

In a nutshell, here are four potential benefits, provided the recommendations are carried out (?):

1. Expanded access to telehealth services — This would allow telehealth visits, in which people virtually interface with a provider, help more patients get the care they need, including prescriptions for medication-assisted treatment where appropriate. This could prove to be of particular benefit to rural health settings where providers are in shorter supply or where barriers like travel distance make it hard for people to meet with providers in person.

2. Expanded training and tracking — This would encourage the development of a more uniform standard of care where opioid prescribers would be held to greater accountability and also required to attend an education program before renewing their opioid prescribing licenses. It would also require prescribers to use a national prescription drug-monitoring program (PDMP) in order to make opioid prescriptions traceable, helping reduce the common loophole of patients seeking multiple prescriptions from different providers without proper monitoring.

3. Expanded staffing to put more hands on deck — This could allow the Department of Health and Human Services to add staff, and appears to allow the Department of Labor some room to hire staff and shift around some funding in order to direct energy toward the crisis.

4. Expanded awareness and reduced stigma — One of the commission’s key goals is to reduce stigma surrounding opioid use disorder, partly through a proposed media campaign aimed at spreading awareness that opioid addiction can happen to anyone and is not a mark of failure.

Many of these recommendations echo those of the 2015 Interagency Guideline on

Prescribing Opioids for Pain, which the Bree endorsed as part of the ongoing Opioid Prescribing Guideline Implementation workgroup, and also align with the work of our Opioid Use Disorder Treatment workgroup. If you’d like to learn more or attend one of these workgroups, follow these links.

THE “CRUCIAL ROLE” OF MEDICAID

In August, the same Opioid Commission issued a draft report of its recommendations, which New Yorker writer Amy Davidson Sorkin noted “demonstrates the crucial role that Medicaid plays in addressing the crisis, and the program’s still greater potential for combating it.”

This, says Sorkin, helps offer an explanation for the tough time Mitch McConnell had garnering support for proposed ACA repeals that called for deep cuts to Medicaid, particular from those colleagues representing states feeling the deepest effects of the opioid crisis.

A CAUSE FOR CAUTIOUS OPTIMISM

As we wait to see how the next steps will play out, there is reason to be optimistic. No matter how you slice it, declaring the opioid crisis an emergency of any kind does, at long last, do one thing and that is make the it a bigger issue. The hope is that doing so invokes a much needed national push to direct pointed, positive energy toward addressing the crisis, bringing it out of the shadows, and helping to save lives.

Read more stories on the topic here:

- NPR | Trump Administration Declares Opioid Crisis A Public Health Emergency

- Vox | Trump just declared a public health emergency to combat the opioid crisis. Here’s what that will do.

- Harvard Business Review | To Combat the Opioid Epidemic, We Must Be Honest About All Its Causes

Emily Wittenhagen

Recent Posts

Archives

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- September 2021

- August 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

Recent Comments